Women in banking: customers

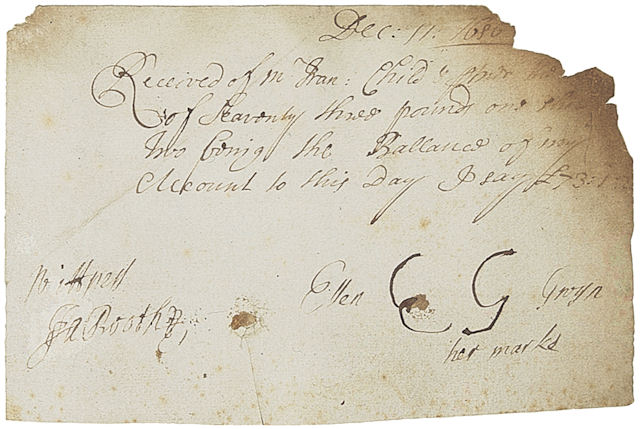

Image: banker’s receipt signed with her initials by Nell Gwyn, 1686 © RBS 2018

Although in later generations women came to prominence as partners, and eventually staff, of banks, their longest-standing role in banking has been as customers.

Our earliest female customers

Women appear as customers in the earliest surviving set of bank records in Britain, the ledgers of goldsmith-banker Edward Backwell dating from the early 1660s. In most cases these were women who had gained their money by inheritance, from a deceased father, husband or other male relative.

One 17th century woman whose wealth had been obtained through a different route was Nell Gwyn, the most famous mistress of King Charles II. She was a customer of Child & Co in the 1670s and 80s. Although by that time her involvement with the king had brought her enough wealth to need a bank account, her disadvantaged upbringing was exposed by her lack of literacy; the archives of Child & Co show that she was barely able to sign her own name when endorsing her account records.

Eleanor Coade

It remained unusual for women to earn their own wealth, long after Nell’s death in 1687. One who did – and who was a customer of our constituent Drummonds Bank – was Mrs Eleanor Coade (1733-1821). She invented a type of artificial stone which could be cast into elaborate shapes, and was used for architectural detail on buildings as well as urns, statuary and other garden features. This material, known as Coade Stone, made it possible for the wealthy to source elegant embellishments on a far larger scale than ever before, and it became extremely fashionable.

Mrs Coade was born in Dorset but moved to London, where she set up her factory in 1769. Although known as ‘Mrs’, this was merely a convention to lend her an air of respectability, given that her status as a businesswoman was rather unusual at the time. She was in fact unmarried.

Mrs Coade held a Royal Appointment, and her work featured on St George’s Chapel, Windsor as well as the first Royal Pavilion at Brighton. Over 650 of her pieces survive today, all over Britain as well as in Canada, the United States, Brazil and the Caribbean.

Florence Nightingale

Although a great proportion of women in the 19th century worked to earn their living, most of them received wages that were too low for them to need a bank account, since banks at that time generally only catered for the wealthier classes. It remained the case, therefore, that most female bank customers held their wealth without employment.

One of our most famous female customers of the 19th century did come from a wealthy background, but turned her considerable energies towards employment, and in the process, changed the world. She was Florence Nightingale, who is widely recognised today as the founder of modern nursing.

Florence’s background of privilege meant that it surprised many when, at the age of 25, she announced her intention to enter nursing. By that time she was already actively involved in working to improve the plight of the poor, and her knowledge as a nurse enabled her to expand her capacity to do good in this field.

She is best known, however, for her role in the Crimean War (1853-1856), where she led a group of volunteer nurses in efforts to make enormous improvements in conditions for wounded soldiers. It was here that she earned her famous nickname ‘the lady with the lamp’.

Florence Nightingale was a customer of Glyn, Mills & Co. In 1872 she wrote to her bankers, thanking them for ‘all the kindness you have shown and trouble you have taken – more especially at the time of the Crimean War 1854-6 when I am aware my account with you was a very troublesome customer.’

Married Women’s Property

Before the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, women’s property automatically came under the ownership of their husbands, so a married woman could not own property in her own right. Many banks required married women to submit a form of authorisation signed by their husband before they could open an account. Some banks even passed by-laws barring women from buying their shares. In other banks, however, women – particularly widows and orphans of moderate means – became very well-represented among the shareholders. This was because in many cases their trustees or advisors saw bank shares as a safe way of securing a quiet, stable income.

The 20th century

The growth in female employment during and after the First World War naturally led to increased numbers of women becoming financially active. In the same period, banks became more seriously interested in attracting customers with smaller savings and incomes, including – for the first time – many women.

In 1967 The Royal Bank of Scotland became the first clearing bank in the UK to introduce a savings stamp scheme. Stamp machines were installed in workplaces, schools, social clubs and hospitals, making bank savings accessible to a whole new range of people, not only by encouraging saving on a small scale, but also by making the service available outside the bank environment. This was a recognition that for many people – perhaps particularly women – a bank branch was a foreign and potentially intimidating place. At the time of the launch, the Bank’s deputy general manager Alexander Robertson said ‘We want to break down the marble pillar image of a bank. With the stamp machines, people will be able to save money 24 hours a day; and we hope that, once they come in, they will find it a nice friendly place.’

Ladies’ branch

At about the same time, one of The Royal Bank of Scotland’s competitors – later to become its partner in merger – was trying a different experiment in attracting female customers. In 1964 National Commercial Bank of Scotland opened Britain’s first ‘Ladies’ branch’, located above a normal high street branch in Edinburgh’s West End.

The branch was the idea of David Alexander, the bank’s managing director. He had seen a similar operation on a visit to New Zealand, and brought the idea back to Scotland, where he thought female customers might appreciate the opportunity to conduct their banking business in an office run by and for women. One early newspaper report described the branch as ‘an all-female world of gold hand-printed wallpaper, huge mirrors, make-up tables and pink-fitted powder room’. Less superficially, though, the branch was genuinely striving to meet customers’ particular needs; it was a recognition that many women were handling their own financial affairs for the first time, and might need – initially, at least – some extra help in doing so effectively.

From the outset there was disagreement over the desirability of segregating the sexes in this way. Some people suggested it was patronising. Others believed that even female customers would rather see male bankers behind the counter. Nevertheless, despite the controversy, the branch settled in as part of National Commercial Bank of Scotland and – after the 1969 merger – The Royal Bank of Scotland. The branch remained open until 1997, although in later years men were no longer officially barred.

Recent decades

In later decades of the 20th century, banks became far more sophisticated in tailoring and marketing products to various categories of customers, including women. This came about partly as a result of the marked diversification of banking business which occurred from the early 1970s onwards, which led to banks playing a wider range of roles in people’s financial lives, from mortgage or loan provider to account custodian, insurer or stockbroker. It was also a natural consequence of the growing diversity of the banking workforce; as more women came to work for banks, it became easier for banks to prioritise and understand the interests of their female customers.

Today, most women probably think of themselves simply as ‘customers’ rather than ‘female customers’ of their banks. As banks strive to meet the requirements of all their customers, gender has become just one of many factors that come together to make each customer unique.