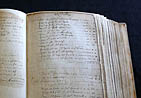

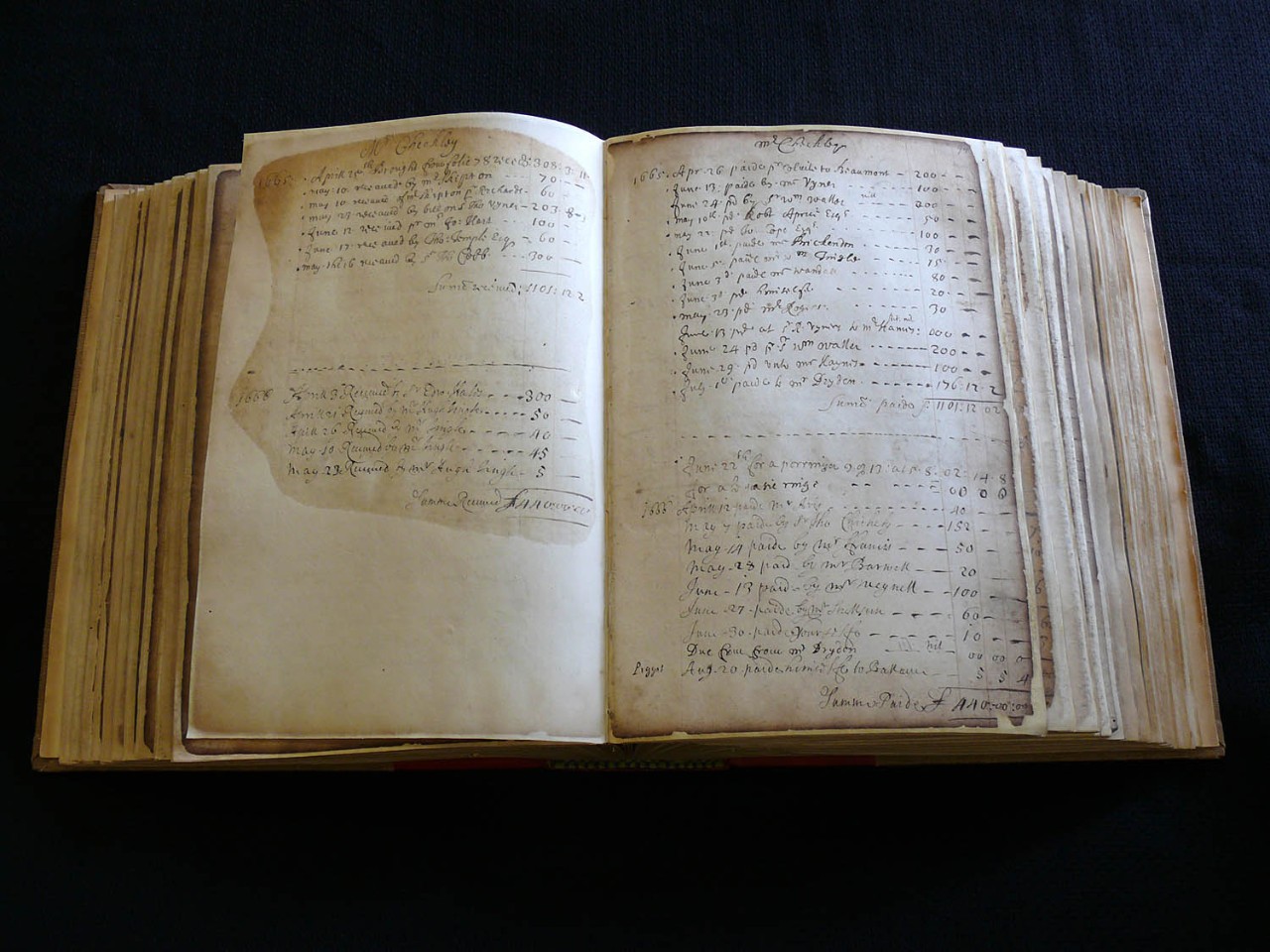

Object 71: Customer ledger, 1663-74

Bound in leather, written on handmade paper by quill pen. Conserved and re-bound. 279 folios detailing customers' accounts using double-entry book-keeping. 330mm x 262mm x 90mm. © RBS

This is a customer ledger of Robert Blanchard, one of London's first generation of bankers. Plenty of interesting transactions are recorded in its pages, useful for historians of Restoration London. Even more intriguing, however, are the gaps around the middle of the two pages shown here, and on plenty of others throughout the volume. Each one coincides with the same period, around July 1665 to February 1666. The ledger seems to suggest that for eight months in 1665-66, nobody in London bought, sold, borrowed or lent anything at all.

The mystery is easily solved, for these months were among the most famous, and terrifying, in London's history. Plague stalked the city's streets, claiming the lives of over 100,000 people. The entire royal court moved to Hampton Court, and thousands of Londoners likewise fled to the country. Merchants who had not been driven out of the city by fear were dragged out by economic necessity, as not enough customers remained to keep their businesses going. London shut up shop.

| it must have felt like the world was ending

It is not known what Robert Blanchard did during those difficult months. Some bankers closed their businesses and moved out of town until the danger had passed. Blanchard may have been one of them. Alternatively, he may - like the famous diarist Samuel Pepys - have stayed in London throughout, the gaps in his ledger merely illustrating how economic life stopped in those months.

We know more about what happened to him in the next calamity that befell London, barely six months later. In September 1666, fire ripped through the city, demolishing 436 acres' worth of streets, homes and businesses. To a population that had only just emerged from the ravages of plague, it must have felt like the world was ending.

In the immediate calamity, Blanchard was lucky; the fire stopped just short of his premises. In the longer term, however, severe consequences had to be faced. Many Londoners left the capital for good. Tradesmen who had served them went out of business, and this had a knock-on effect on Blanchard's business. His bank did not fully recover until the late 1670s, by which time he'd taken on his stepson-in-law Francis Child as partner. Soon afterwards, the business became known as Child & Co.

Child & Co carried forward within it the knowledge of having survived the extraordinary, apocalyptic days of 1665 and 1666. Perhaps this gave it courage to face the future. Even so, it's unlikely that Blanchard or Child could have foreseen what we now know; that today, well over 300 years later, their bank still exists - the oldest name in British banking - as part of today's Royal Bank of Scotland.